A look at genre-categories: Puzzling out puzzle games.

It's time for more genre theory. This time with a focus on the ever-expanding catalogue and terms to describe video game genres. With each new idea, or combination, of either visual representation or gameplay mechanics, another subcategory is created.

Genre theory is a topic that I've previously touched upon: My favourite sub-category for games still being 'comfort games'. While not as detailed, I also brought up elements that are of importance for ‘horror games’ and ‘detective games’ respectively - And, in a way, this article could even be regarded as a bit of an unofficial follow-up on the latter. I've found myself thinking more and more about the category, or genre, 'puzzle game' and how it is (and isn't) used to define a game.

Most have an inert understanding discussing the term “puzzle”, though, even there we’re already working within a set of parameters that try to encapsulate the many different types of puzzles. Moreover, it seems that a pretty strict and clear-cut definition of the term puzzle could never be achieved, mostly due to the vast variety of puzzles (Browne 23).

More generally, a puzzle can be defined as “a task that is fun and has a right answer”, or alternatively “a question which challenges people to solve […]” (23). Browne argues that a puzzle in itself functions as “a two-player game played between the setter and the solver” (23). It is important to note that the goal of the setter is not to win, but to provide an enjoyable and entertaining experience for the solver (23). Therefore, the least complicated answer to “What even is a puzzle game” should simply take upon this concept and then further gamify it in some form:

“Successful video puzzle games such as Tetris and 2048 typically ‘hook’ the player with such cycles of challenge and reward, as they are presented with continuous sequences of interesting subproblems to solve, each of which feeds the next, until the solution is achieved. […] These games also tap into our natural betting and risk assessment instincts – what happens if I put that piece here? Or there? – which builds a sense of anticipation to see whether the next piece will fit the current plan. […]” (27)

While the two examples provided by Browne already function as a decent example, as both of those games are quite well known, I wanted to elaborate on this concept with another game:

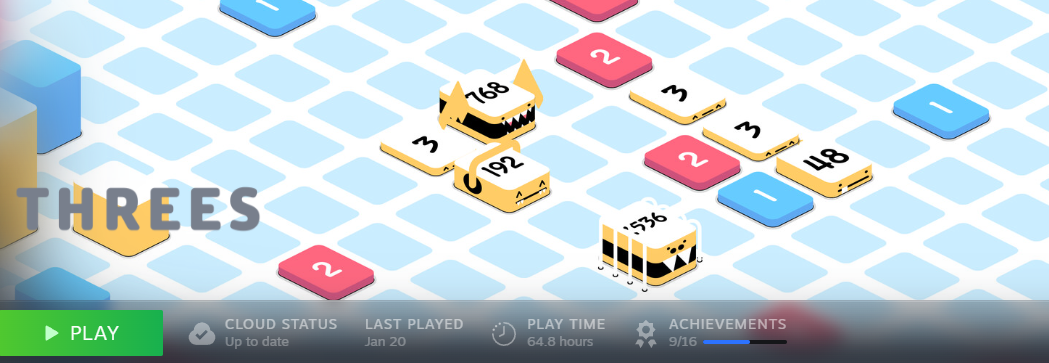

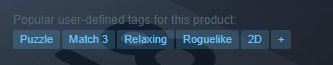

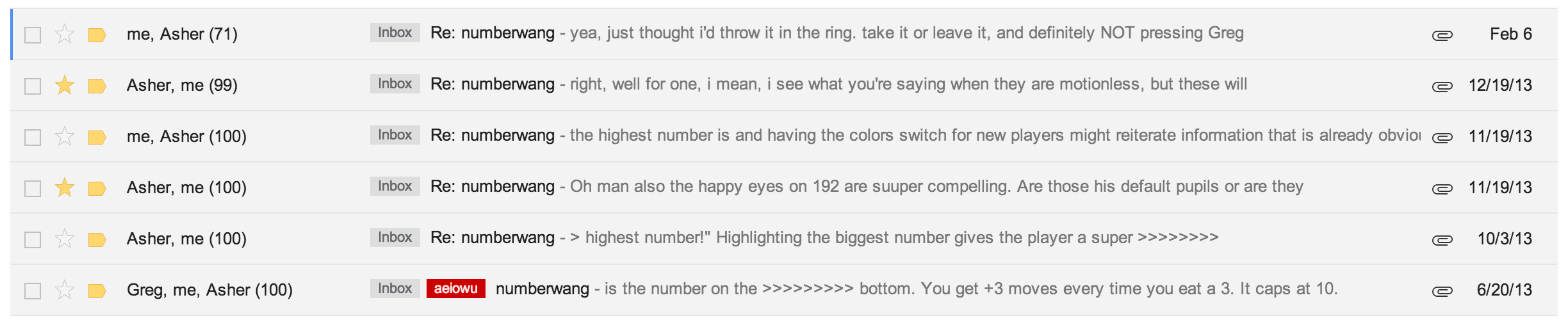

Threes! by Ashner Vollmer and Greg Wohlwend, with music by Jimmy Hinson, was released originally for IOS back in 2014, weeks before 2048 had even existed. While the game managed to gain quite the popularity, it had ended up getting surpassed by an imitation of and imitation of itself (Casti, Ngyuen). The gameplay between those two games is certainly different, 2048 is regarded as a more simplified version of what Threes! had to offer, as stated by Taylor Casti, Kevin Nyguen, and the team behind Threes! themselves.

Admittedly, I have to agree with them. While I've managed to beat 2048 multiple times, after just a few days of trying, I've not yet managed to beat Threes! at all. The game itself is a sliding puzzle, where you continuously create multiples of three, with the main goal being to reach a high score. Each sliding step will either provide you with a standard card (blue [1], red [2], white [3]) or a special card (6, 12, 24, ...). A game over will be reached when there are no spaces, and thus, no moves, left for the player to make.

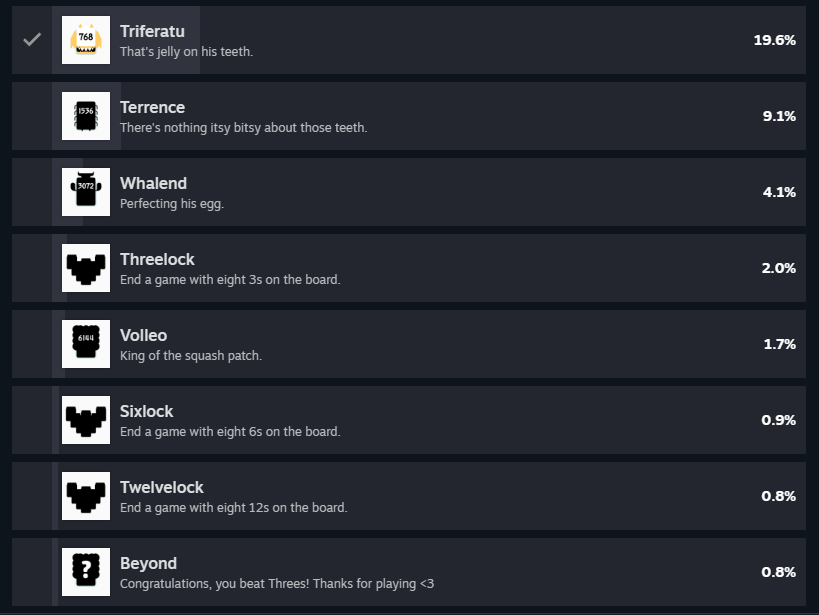

An example of a the first few moments in a a game of Threes! [in dark mode]

On top of the UI, the player is able to see the colour of the next tile. This allows for better planning and careful movement while rearranging the tile-board. The challenge of the game being "How will I reach the next highest number?" or "How will I get out of this 'bad' situation?".

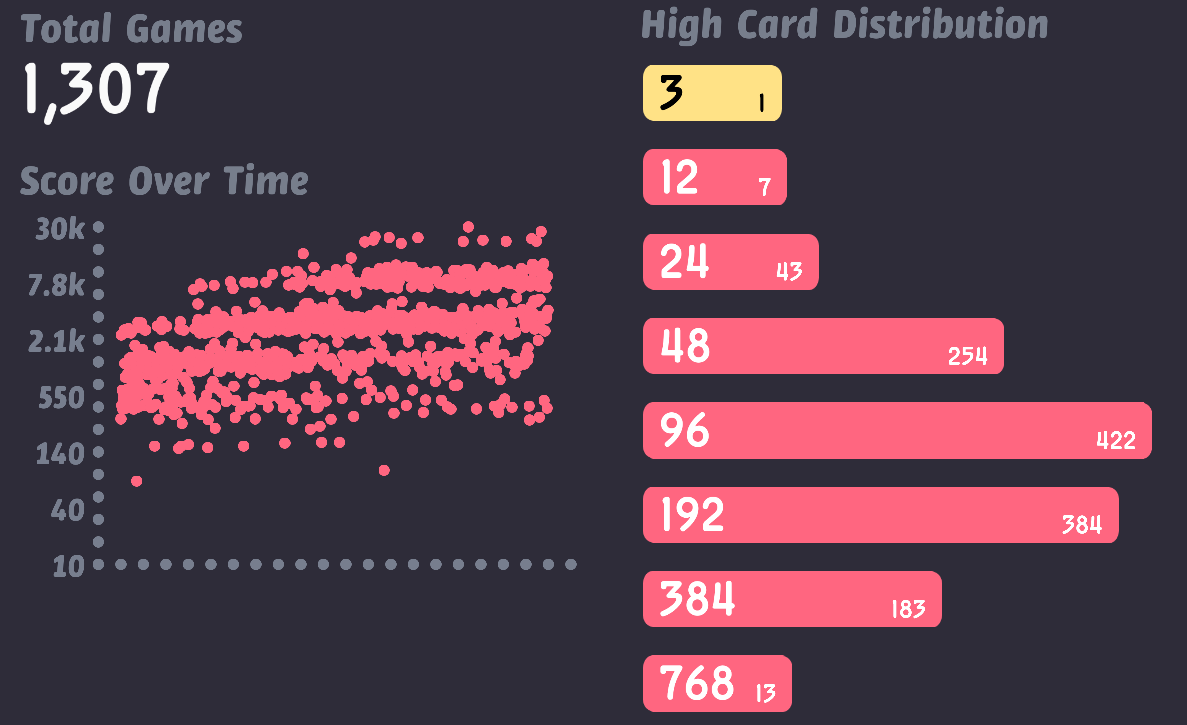

The game also includes a stats-board, which ensures that all the players accomplishments can be revisited.

To beat Threes! one has to combine two "Volleo" tiles [6144] to reach "Beyond" [12'288]. The initial puzzle is simply the drive to "find a way", while the 'gamification' of that concept includes the element of the high score. So far, it seems that even now, after a decade, that beating Threes! itself is near impossible - or that's what I am able to infer while looking at the game's steam achievements.

All of this to say, Threes! certainly encapsulates everything that we'd established for a puzzle game. You start the game, you try and solve the puzzle. There's nothing else.

Accordingly, the book “Video Games: An Introduction to the Industry” defines a “puzzle game” as something that is “identified by puzzle solving activities that can, amongst other things, test logic, memory, knowledge, and sensory sensitivity” (Bossom & Dunning 41).

However, it is at this point, where things become uncertain. How much puzzle solving activity is needed to categorise a game as a puzzle game? While looking into the different definitions of puzzle games, I've come across multiple opinions, which in itself reflects the vagueness that the term puzzle already comes with.

In Dr. Ernest Adams' book "Fundamentals of Puzzle and Casual Game Design", he notes:

“[…] puzzle solving is the primary activity, though puzzles may occur within a storyline or lead up to some larger goal [...] Because most puzzle games are abstract the game world does not simulate a real place, and usually the player does not enact a role within the world. There are exceptions: in Sokoban, the player takes the role of a warehouse custodian and has an avatar, but her duties are limited to pushing crates around. Unlike designing most other games, the process of designing a puzzle game does not involve enabling some kind of fantasy such as being an explorer or a race car driver. Many puzzle games take place in 2D worlds with simple top-down views.” (Adams 7)

While this certainly is the case for games such as the aforementioned Threes! and "Tetris", I don't think that it is enough to truly capture the presentation and scope that a puzzle game can actually possess. Considering the book's title, it seems that he already had a rather specific idea regarding the 'subcategory' that these puzzle games would be a part of; Considering that in his other book "Fundamentals of Adventure Game Design", he notes that "[m]ost adventure games consist of a sequence of puzzles [...]" (Adams). This would imply that adventure games themselves, due to their primary activity: "puzzle solving", should be considered puzzle games - which would then counter Adams previously established statement that a puzzle game would not "involve enabling some kind of fantasy" or "take place in 2D worlds with simple top-down views".

My own doubts regarding Adams' definition are rewarded, when comparing these notes once again with "Video Games: An Introduction to the Industry", where it is noted that a puzzle game "[...] can be experienced through many different gaming scenarios, some bite sized and others far more immersive. The look and game style can be bright and colorful, with matching sound effects, […] or woven into stories full of ambiance and mystery where the player needs to understand complex narrative links to solve and conclude the game […]" (Bossom & Dunning 41).

Looking back at my previous article on detective games, I've come to realise that I've not really engaged as much as I should have with the question "what makes something an [insert genre] game?". Instead, I had placed my focus on gameplay mechanics, and overlooked the fact that the detective game is potentially more dependent on its setting and narrative than its gameplay. The reason many detective games are overlapping the category of puzzle game, lies in their inherent goal to solve a mystery, which in itself is often presented as a puzzle, though, it really isn't as much a necessity as I had initially thought. In that initial article, I disregarded anything that did not resemble "deductions". To quote myself:

"While I always enjoy a good detective story, I do have issues with certain detective type games due to their lacklustre form of gameplay" (par. 13).

It was a rather harsh assessment. It made sense, while writing, because I was so focused on gameplay that would resemble the science of deduction, but I do feel like I hadn't given this as much thought as I should have. Interestingly, I did mention the Professor Layton series - and to be completely honest, I think it's a great example that showcases what I've initially missed.

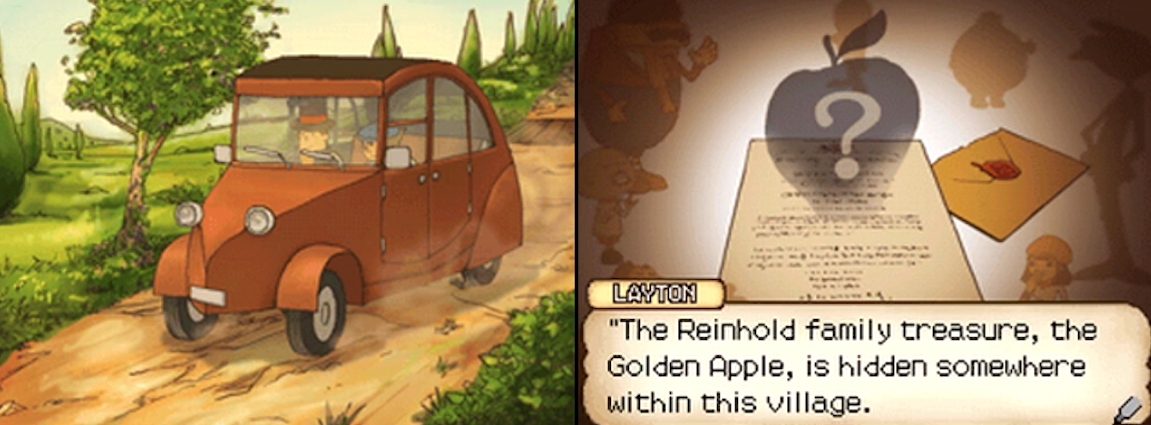

The Professor Layton games by Level 5 are, in their most basic form, just a collection of logic puzzles. The gameplay is to find these puzzles in the world, and to solve them. However, the world itself in these games also offers an additional layer of intrigue for the player. The game's initial hook, too, lies in a mystery that Layton wishes to solve. In Professor Layton and the Curious Village, the hook is an inheritance dispute and the mystery of the "Golden Apple", which is considered to be the family treasure:

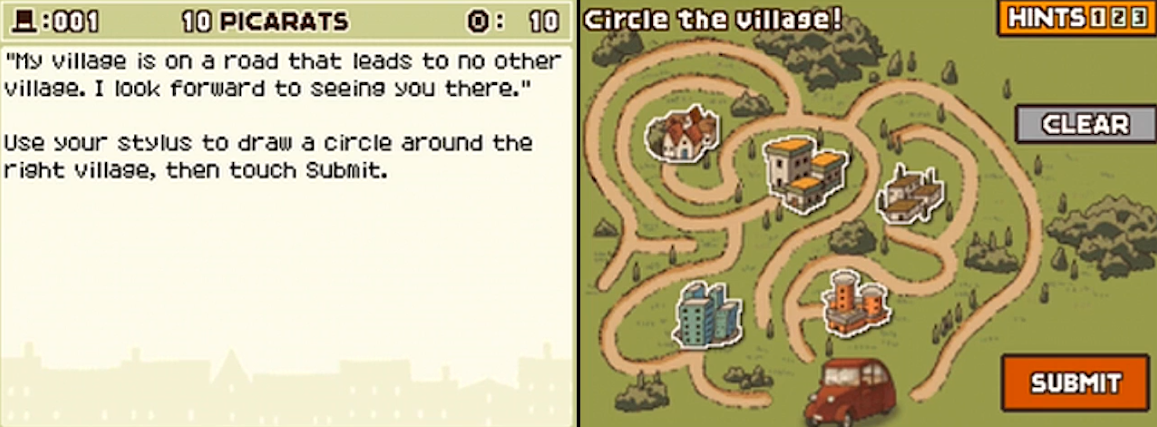

This initial hook, as well as the development of the story are certainly providing enough intrigue in the player that they'd try to finish the game and to find its answers, but the gameplay loop focuses less on that overarching narrative, and more on actual logic puzzles. Some of them are more directly tied to the story at hand - for example the very first puzzle, which asks of you to find out where the village is actually situated:

Other puzzles... are not like that. You find yourself tapping on the DS touchscreen and, suddenly, there'd be another puzzle. It has nothing to do with the plot, it has nothing to do with anything at all, it's simply another puzzle for your collection. It's simply that: a means for you to get more puzzles to solve.

Overall, these kinds of games don't want you to think of yourself as being a detective. No, they want you to think of yourself as being a puzzle solver!

A game such as Professor Layton perfectly surmises a puzzle game as noted in "Video Games: An Introduction to the Industry", the colourful and mysterious story functioning as a means through which one will encounter the actual puzzle collection. In this specific case, the narrative of the game, the initial mystery of the "Golden Apple", presents this overlap between those categories "detective" and "puzzle", which is presented through the gameplay.

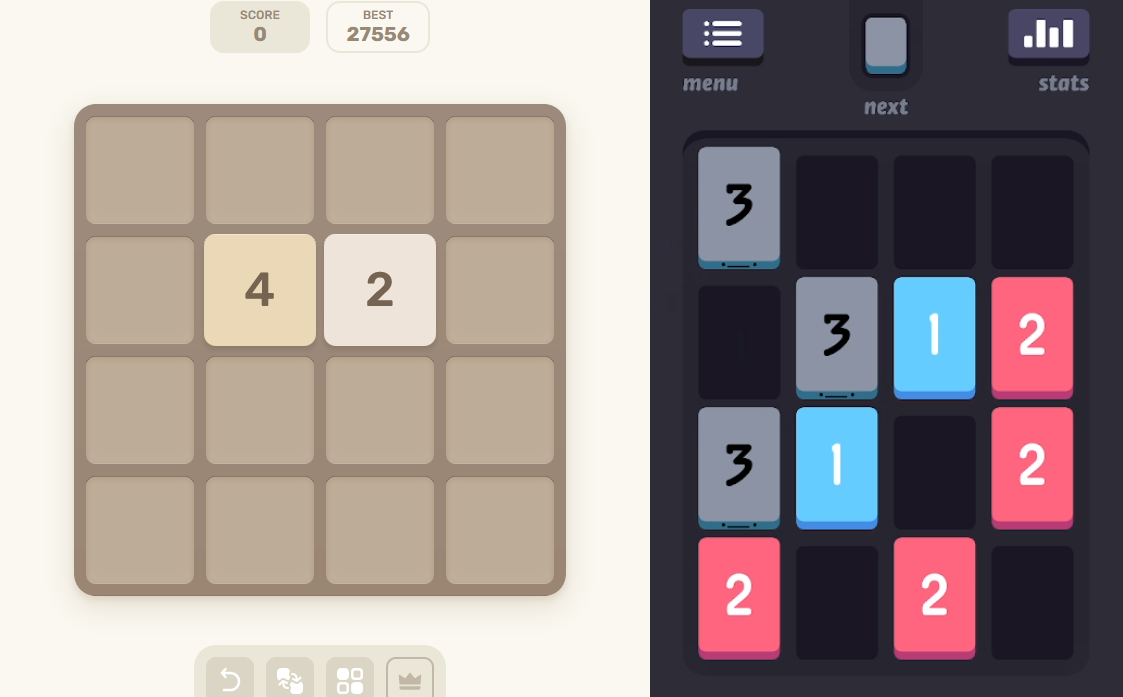

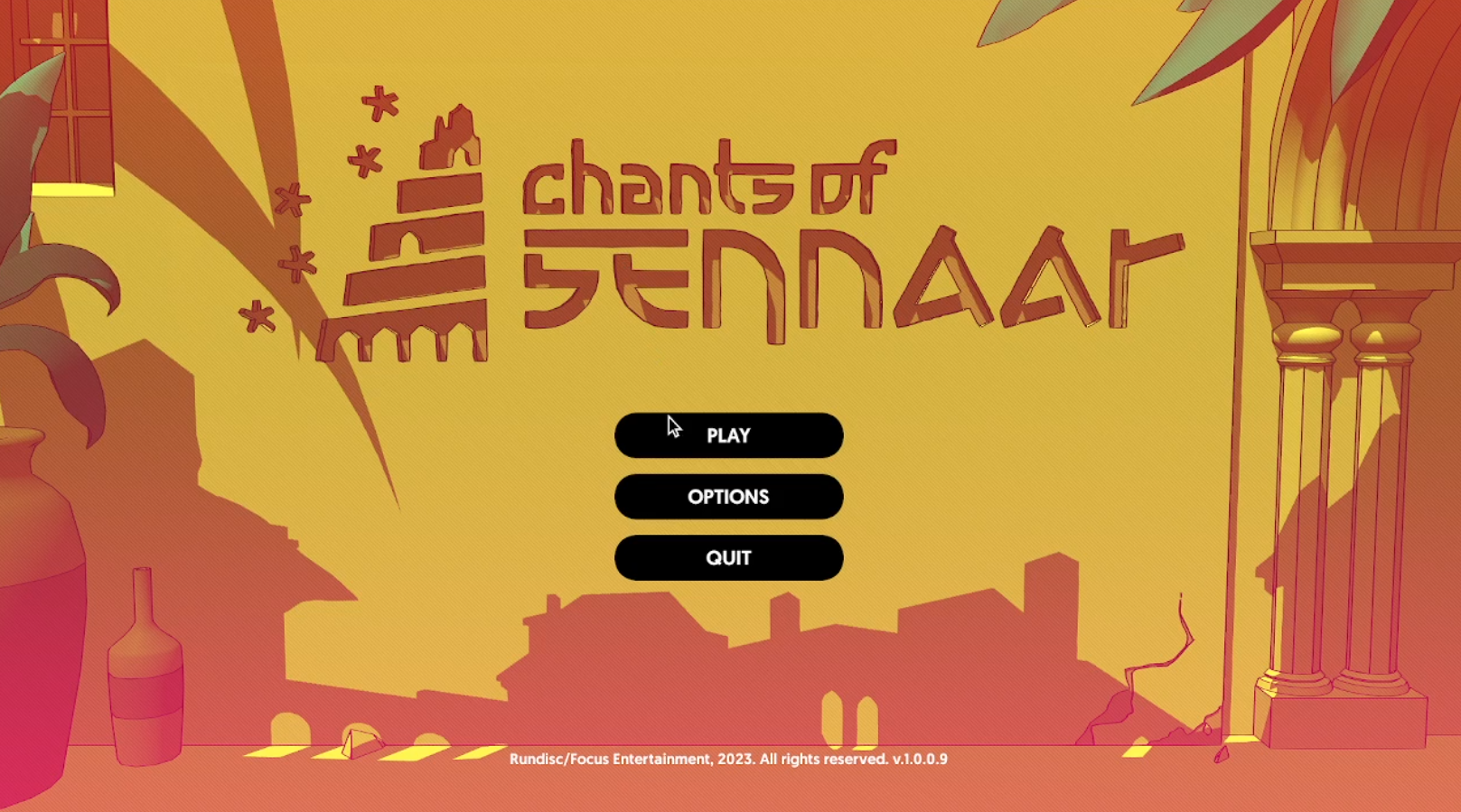

It's a fun reminder, even to myself, that all of these categories are vague and subjective. Especially when looking at steam user tags, which are more or less accurate - but not always official. It is an amalgamation of tags that will include whichever bit of the game someone deems important.

Puzzle: A succinct explanation of the expected gameplay. [...]

Match 3: A more specific definition of what type of puzzle should be expected when playing this game. In this case referring to the concept of moving tiles on a puzzle board as a means to solve, or match, them correctly.

Relaxing: This tag seems to function as a means of capturing the game's atmosphere while playing. It implies a certain calmness of the mind and a lack of anxiety for the players. Though, just like the term "comfort game" its application is heavily reliant on an outside element, namely the emotional response of the player character.

Roguelike:

"[...] with a Roguelike, traditionally you would not retain any progression when you fail. You would always start with a completely blank slate [...]" - Sherigan (PoT - Hades (2020), 20:42 - 58)

While technically correct, each failure state in Threes! will lead to a game over, where one will have to start completely anew with a newly and randomly assigned set of starting tiles, it certainly seems an interesting addition as a means of explaining the form of gameplay. This would imply that most puzzle only games with failure states could also be considered a Roguelike...

You heard it here first, Tetris is also a Roguelike, even if there are no elements of dungeon crawling, or any gameplay features that resemble the game Rogue from 1980.

2D: A tag that explains the game's visual choices, in this case, like many tile based games it's rather flat. The game uses a "top-down" perspective to visualise its puzzle. Though, if I may nitpick this: The game actually has its tiles and world shown as 3D pieces. The front of the tile usually including a face, while the top of the tile showcases the actual number. In contrast to 2048, Threes! shows more visual depth.

Overall, I do believe that most of these tags are quite fitting. My personal gripe only being the "Roguelike" - tag, but even there, I can still see why people might use this term; The familiarity of certain terms can lead to a broadening of their meaning. It's absolutely fascinating.

And now it's time to get quite hypocritical and judge these tags and their usage, while I am also talking about puzzle games. - I, too, have biases and opinions and I'd like to share some of them and present my argument.

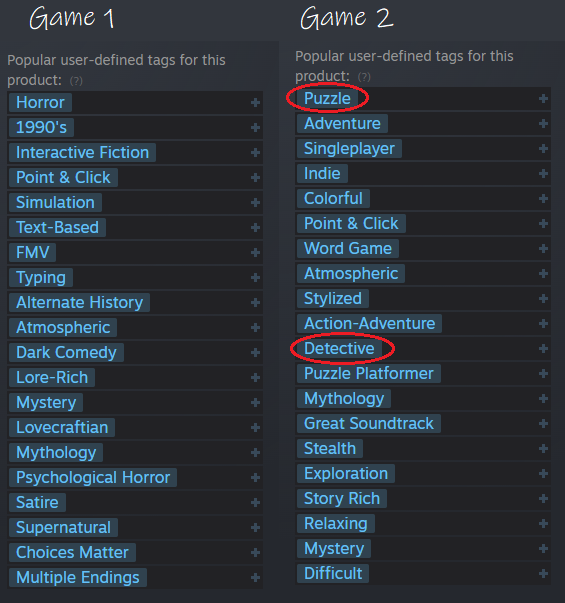

The reason, why all of this had been on my mind, had barely anything to do with Threes!. Instead, it's about two games, that I'd categorise as puzzle games, which place a lot of thought into their presentation and integration of their puzzles within their lore. However, interestingly, when looking at the steam tag lists, only one of these games should even considered to be either a "puzzle" or "detective" game:

I don't want to dismiss the potential uses these lists have when trying to surmise what encompasses a game, but I do feel like this perfectly showcases also the limitations of such a feature. These lists only show the elements, which people have prioritised.

Game 1 was generally attributed multiple tags, which try to describe a theme, or the game's presentation, while barely touching upon the subject of gameplay. Meanwhile, Game 2 has been attributed a more evenly mixed selection of tags that focus on both gameplay and presentation, though lacking in thematic depth. This is not to say that these other elements are completely bereft, solely, that the individual users had placed their focus primarily elsewhere.

Hearing noises? Seeing things? Call Home Safety Hotline! Our operators are standing by, waiting to give you the answers you need to protect your home from all manner of pests and household hazards. ("About this Game" , HSH Steam Store Page)

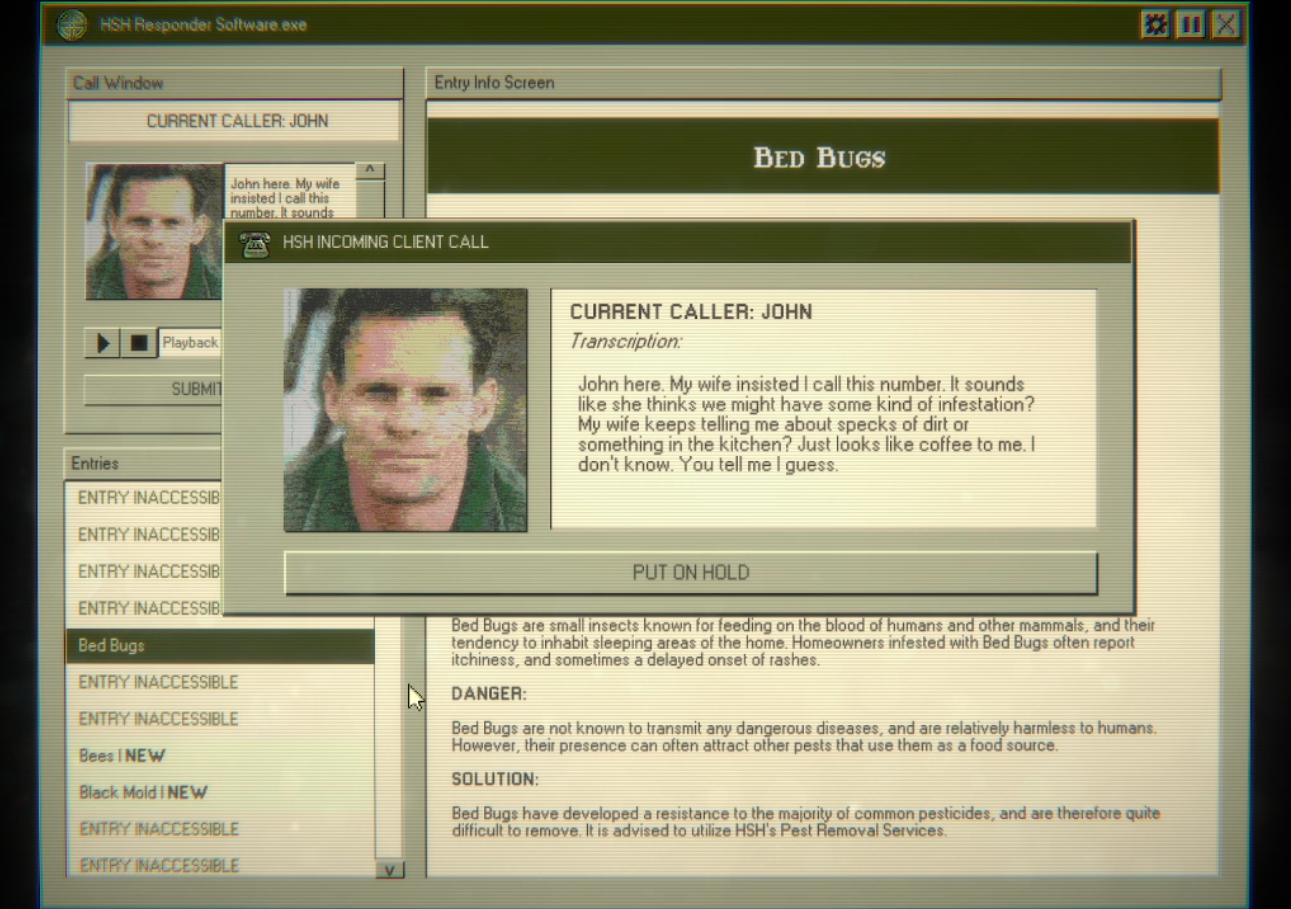

In Home Safety Hotline the player has to answer any incoming calls and provide them with the correct answer regarding the hazards that the customer is experiencing.

The player is solely at their office computer, where they are provided with a catalogue of hazards, to which they can refer to while trying to help the customer. There is no time limit per call, solely, a lovely little tune that plays, while your customer is holding their call.

The goal of the player is to pick the correct hazard, when helping your customer. Thus, the player has to carefully read through the given transcripts and records and find the matching element. The game keeps track of your accuracy and responds accordingly. This is probably where the tags such as "interactive fiction", "multiple endings", and "choices matter" come in. On another note, I wonder why the tag "typing" even made it on this list, as the player never really has to do any typing throughout gameplay.

With this in mind, I realise that part of the issue might simply be that people don't know how to describe your actions in this game. Instead, the focus is placed on elements that are far more easily established, like its aesthetic, it's lore, and it's overall vibes!

Horror: A rather apt tag overall, when comparing it to the game's own description as "an analog horror" piece ("About this Game"). It functions as a descriptor of the themes and atmosphere that can be expected. It does not elaborate further on what type of horror is conveyed (or at least not within the first few tags, though, the larger list does try to specify that), but it conveys that spooky things will be happening at some point.

On a personal note, I do think the green and the words "analog horror" really activated my interest in this game - like a sleeper agent hearing their activation phrase, I was ready to dive in.

To be fair, the colour green has been often associated with computers, which is, according to TVTropes, due to a specific type of monitor: the IBM 5151 monitor ("Cyber Green" TVTropes). However, I do think it is funny how my personal association still fit the theme itself, and the monitor on the title screen of the game does not resemble the 5151 monitor either...

1990's: This, at a first glance, seems pretty apt as well. For one, it reflects the previously mentioned "analogue" within "analogue horror", but it is also proven to be correct in a more literal sense - the game seemingly takes place in the year 1996.

Another slight tangent, but I do think this tag in itself is fascinating. I end up asking myself if this tag is meant to capture games that were "initially" released in the 90s? Which this one isn't. If it is meant to encapsulate games that take place during the 90s? Which this one does. Or if it is meant to include all games that are made to look like they were made in the 90s? Which this game also kind of does.

Interactive Fiction: This tag attempts at explaining the gameplay loop. It, like the other two is rather vague. Generally, when people talk of interactive fiction it is often put together with terms such as "Choose Your Own Adventure Books" and for games "Visual Novel" ("Interactive Fiction").

This tag implies that the player has the ability to make their choices and that these choices will lead to different outcomes.

Point & Click: Another attempt at explaining the gameplay loop. The player points at something (that is on the screen) with their mouse and then gets to click that thing. The game makes use this as a means of navigating the different settings in the game, so pointing and clicking seems apt enough.

This still doesn't explain what the player has to do, only how they will have to navigate their game.

I am fascinated by these initial tags, since they are so different than what we've seen for Threes!. Naturally, there is something to say about the fact that Threes! does not present any additional elements that could potentially overshadow its puzzle nature. In contrast Home Safety Hotline seems to thrive solely on its visual aesthetic and theme, with only the smallest hint toward its potential gameplay with the tag "interactive fiction"; A tag, which I still believe is barely adequate when compared to the vast pool of alternatives that we could have chosen instead.

So, then, what is the player doing, when they start to play Home Safety Hotline?

At its most basic it's just one thing, it's answering the question asked by each client: "What is going on in my house?"

A look at the in-universe "Television Commercial" for the Home Safety Hotline.

They tell the player their troubles and through the context clues given, the player has to make the correct guess about the culprit. The player is given access to a database that has the information needed to find the correct answer; to solve this... puzzle.

Previously, I mentioned that a puzzle could also be defined as “a question which challenges people to solve […]” (Browne 23) - and the main gameplay loop of Home Safety Hotline covers exactly that.

It's a list of questions, which the player has to solve. This is the main reason why I think the term "interactive fiction" is insufficient to explain this game. These "different" choices just amass to be either 'correct' or 'incorrect'. Incorrect choices will not lead to an immediate game over, but they will influence the players ending.

If the correct answer to "What is going on in my house?" was "Bees" then any of the other answers would lead to the same outcome - namely: The player got it wrong. There is no other branching path.

Home Safety Hotline IS a puzzle game. I am actually bewildered that no other user on steam has tagged the game as such!

There might not be a numbered high score, but there is an accuracy window which appears at the end of each workday, which is where they'll see how well they've actually done.

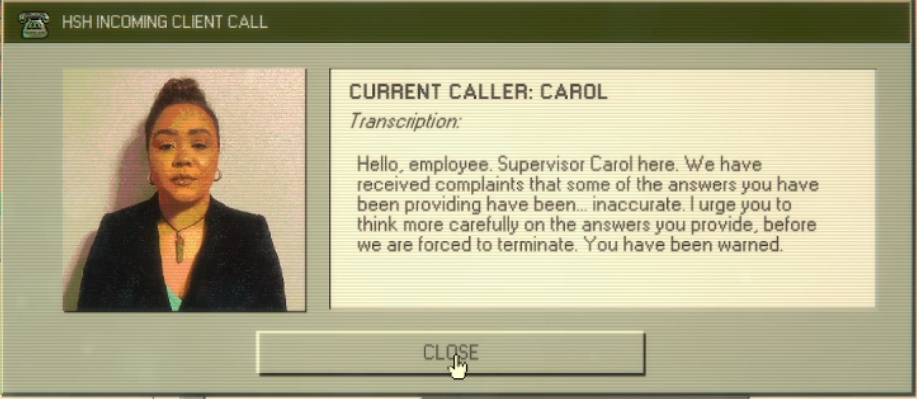

Now, unlike games such as Professor Layton, they don't offer retries on puzzles, you have one chance to make your deduction - there are no (immediate do-overs) and if it's wrong, they will let you know. [Thanks Carol!]

The game does not actually tell you the correct answer, which I appreciate. One interesting bit was that one might learn more about the world itself, if they get the hazards wrong. If the player answered incorrectly, there will be a consequences call, where the aftermath of having received the wrong information will play out. These may vary from "not too bad" to "horrific", which is great world-building that still uses the limitations of its setting to its advantage.

Each day has a set amount of callers and the game itself has a set amount of days. At the start of each day, you will receive a phone call from your Supervisor, who might even give you access to more entries, slowly expanding the set of potential hazards.

That is why people struggle to explain gameplay, because the game is a box of puzzles ready for you to be solved, though, simultaneously packaged in a neat little framing narrative. It's a puzzle collection, just like the Professor Layton games. However, unlike the series, this game focuses on one specific puzzle variant, which is based on deductive reasoning, or specifically: syllogism.

"A syllogism is a form of deductive reasoning in which a conclusion is drawn from two or more premises. This logical structure consists of three parts: a major premise, a minor premise, and a conclusion." (Syllogism)

In the case of the puzzle structure for this game, the conclusion is what is asked for:

Major premise: There is a hazard in John's house, potentially an infestation. There are specks of dirt (or something), which kind of look like coffee.

Minor premise: Is provided by the data entries from the Home Safety Hotline. There, the player may find the information that they're looking for. "Homeowners with [...] commonly report seeing droppings that appear similar to coffee grounds." (HSH Responder Software.exe)

Conclusion: Therefore, the hazard at John's house is [...].

Personally, this type of puzzle reminds me of logic grid puzzles. They were a favourite of mine in my youth, since I've always enjoyed deduction focused games. The steampage for this game, too, notes that the gameplay itself is heavily deduction based:

"Correctly deduce what's in your callers' homes or else leave them to suffer the consequences." (HSH Steam Store Page)

Now, with all of this in mind - I find myself still perplexed by the fact that none of the tags cover the terms puzzle, or detective. Though, the latter I understand slightly, as the narrative and story aspect certainly does not involve any detective work - or does it?

Well, in a similar fashion to the Layton series, this puzzle box is wrapped in an additional mystery: "What is going on at the Home Safety Hotline?". The framing narrative is what hooks the player and throughout the game are enough clues that imply that there is more to the Home Safety Hotline than initially assumed. Certainly, there is the implied element of horror, and according to the tags, supernatural - but the understanding of that world is solely dependant on the players ability to read these clues. The player isn't a detective according to the game itself, but if the motivation to play this game lies in solving the mystery behind this place of work, then wouldn't that at least imply an on-going investigation?

There is a certain humour to find in this personal endeavour of mine. While I am making an argument talking about the subjectivity of so many of these tags, I am simultaneously trying to make my own case for their use. For example, the term detective, can be both "fitting" and "ill-fitting" depending on an individuals subjective biases and priorities. Is a detective game dependent on its setting and characters? Or dependant on gameplay? - The protagonist is not a detective, but we are using methods that are often associated with them, is that enough? Should it be enough?

Naturally, the answer is: "It's complicated".

The last puzzle game I want to mention here, is actually considered to be a puzzle game according to Steam. It seems that at least this time the people and I seem to agree with one another.

As the Traveler, delve into a world full of mysteries, where Peoples have grown distant, unable to communicate with each other anymore. [...] [E]xplore and solve various puzzles to uncover the mysteries of five different interconnected languages. ("About this Game" , CoS Steam Store Page)

The most notable difference to all games that I've mentioned before [Layton, Threes!, and Home Safety Hotline] is that Chants of Sennaar allows their protagonist full motion. This game places a lot of its gravitas in the visual spectacle that can be achieved simply by allowing the character to freely move around. The camera is given specific placement and movement triggers, which will only move as a means to provide the player with a visual spectacle.

I bring this up due to the initial argumentation given by Dr. Ernest Adams regarding the presentation of puzzle games.

Because most puzzle games are abstract the game world does not simulate a real place, and usually the player does not enact a role within the world. [...] Many puzzle games take place in 2D worlds with simple top-down views. (Adams 7)

The issues with this sort of definition had been brought up here before, but in games such as this - as well as the previously mentioned Professor Layton series - it becomes more evident how narrow such definitions would be. Moreover, it seems like enough individuals seem to have disagreed with this assessment, since Chants of Sennaar has been attributed the quite lovely puzzle tag anyway.

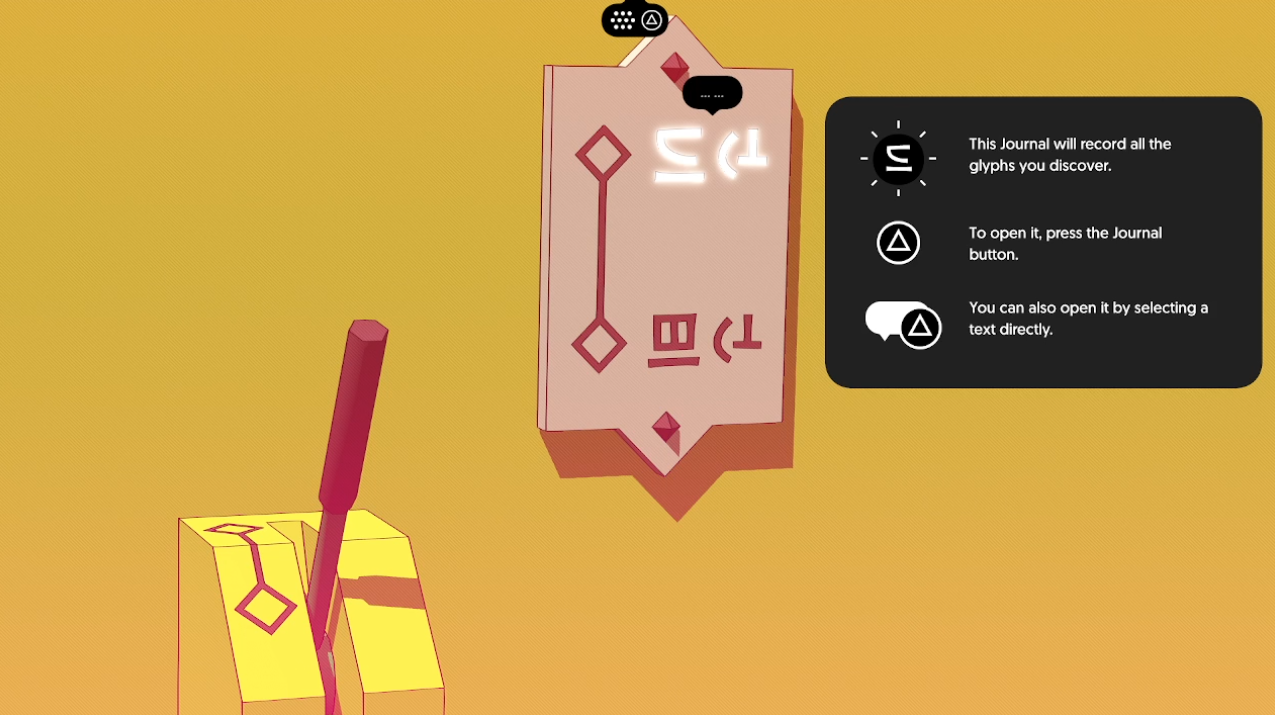

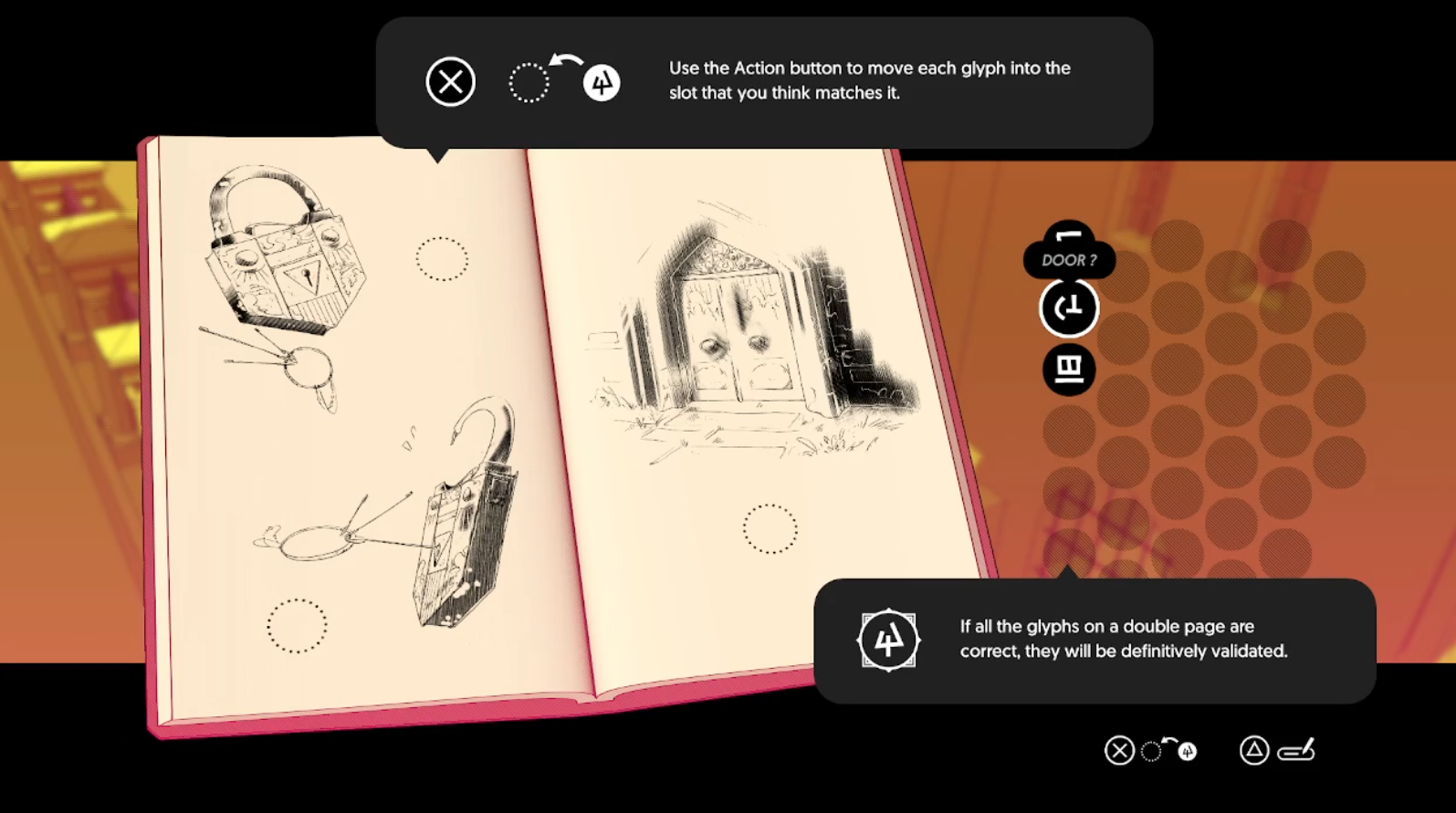

The game begins with the Traveller waking up from slumber. We do not know who or what they are, but they will move out of their tomb and explore their immediate surroundings. There they will come across their first obstacle: a door.

The door is locked. Next to it there is a lever and a plaque. When the player interacts with the lever, they will be given a closer look at the machinery. The tutorial for the main mechanic will also appear, though, that will vanish after the initial attempts.

This is the introduction to one of the game's main gameplay elements, which is to answer one simple question: "What does this glyph actually mean?"

This game, not unlike Home Safety Hotline, has a rather simple core idea - to focus on the players abilities of deductive reasoning, and more specifically (again): syllogism.

Spoiler for the first puzzle of Chants of Sennaar:

Major premise: You are standing in front of a locked door with a lever pointing downward and a two diamond symbol painted next to it.

Minor premise one: The note next to the machinery has a two diamond symbol painted on it.

Minor premise two: The note showcases three different glyphs, with one appearing twice within it's two words/sentences.

Minor premise three: The game suggests that each glyph is given one meaning, making this a phrase: [...][...]

Conclusion one: The note next to the machinery is tied to the machinery, not just by proximity, but also through the two diamond symbol painted on each element.

Conclusion two: The glyph appearing twice implies that this element remained unchanged in either case - in this case: the door.

Conclusion three: Since the door is locked due to the lever being placed downwards, one of the glyphs at the bottom part of the note should be interpreted as something akin to locked or closed.

Conclusion four: If pushing the lever up will open the door, then the remaining glyph could be interpreted as unlock or open.

Now, quite unlike Home Safety Hotline this game does not really allow for mistranslations to remain. For one, the game itself includes another layer of 'security' with its journal pages validating the players input at specific points throughout the game. Moreover, an incorrect result will at some point lead to a lack of progression - to beat the story one has to be able to translate these glyphs correctly.

On a linguistic level, I am fascinated by how much thought was put into these languages. If one is more familiar with language structure and symbolic writings, one can actually make pretty decent deductions simply based on a glyphs structure, even without any additional context given.

However, where this game deviates from both Threes! and Home Safety Hotline, is in the variation of puzzles provided. Chants of Sennaar adds some variation in its gameplay by including stealth sections and the occasional object movement puzzle. These puzzles are far more integrated in the world than they'd ever been in the Professor Layton series, but they are also far more dependent on the world that surrounds them. When recontextualising this with the given tags of the game, this would probably be the reason behind the terms "puzzle adventure", "adventure", and even the slight misnomer "puzzle platformer" - as there really isn't any typical platforming happening throughout the game's runtime. This game has NO jump button!

Personally, I am fascinated by how quickly Chants of Sennaar is accepted to be both "puzzle" and "deductive" game. I assume this is due to the clear indication and direct tie-in of the players deductive reasoning through the visualisation of the Traveller's journal. The fact that any notes regarding the language translations are actually visible on screen. However, why isn't Home Safety Hotline given the same treatment by its players?

I do think there are multiple reasons why things are the way they are.

- As initially mentioned - it all depends on the elements that the individual will focus on. When they recommend a game to someone else - how would they explain it to their friend? I think games such as Home Safety Hotline will always be argued to be "horror" first and "puzzle" second - if at all - due to the fact that "horror" as a theme has such an influence on the perception of a game.

- It is likely, that certain tags are chosen due to an uncertainty and potential lack of precision. This is were I'd put tags like "Roguelike", "Interactive Fiction", and "Puzzle Platformer", as noted during each game's section. While not perfect, those terms signify an attempt done through association. This is often in combination with...

- ... the current cultural context. Terms such as "Roguelike", "Roguelite", and "Soulslike" are used rather freely. Culture shapes our perception of games and how people categorise it. A game with a specific movement set - for example a stamina bar and the ability to dodge-roll - will often be associated with Dark Souls and, thus, the game gains the definition "Soulslike". An eldritch horror piece will often and quickly be categorised as "Lovecraftian", even if the actual Cthulhu mythos remains absent. These associations aren't just means of defining it as clear as possible, but explaining it through a lens of cultural familiarity.

Looking back at my three game examples, I feel like Home Safety Hotline's status as a puzzle game fell flat due to people either being unaware that this form of deduction could be interpreted as a puzzle at all, or that they simply needed something more palpable - Something akin to Threes!; Something that left a visible trace of a puzzle. Meanwhile, Chants of Sennaar's deductions are needed to solve additional puzzles in the overworld. This additional subset of visual puzzles with the added freedom of movement, as well as the more deliberate "solving" state that Chants of Sennaar uses, might have influenced peoples perceptions.

Personally, I remain fascinated by genre-theory and any attempts at categorisation. Especially on platforms such as Steam, where the popular user tags remain highly valued as attempted game descriptions. Initially I decided to focus on puzzle games, because I recognised the similarities between these three games that I've played consecutively, and noted my previous lack if depth in my article on 'detective games' - and now we're here:

I was annoyed and confused by my own struggles to define something 'objectively' even though I was familiar with the fact that these descriptions are heavily based on people's biases.... This reminds me - did you guys know that tomatoes are a fruit, bananas and cucumbers are berries, while strawberries and cherries are not?

The way we categorise things is just another puzzle in itself, actually. Though, this one seems to have more than one accepted solution?

Additional Reading:

For a concise history regarding Threes! and 2048, I do recommend Kevin Nguyen's article published for The Verge. Additionally, I do think it's also interesting to read through Threes! open letter that they had initially posted after seeing these other games appear.

"The Rip-offs & Making Our Original Game" an open letter by Ashner Vollmer and Greg Wohlwend

Primary Sources:

Threes!. Created by Asher Vollmer, Greg Wohlwend. Music by Jimmy Hinson, Sirvo, 2014. Multiplatform (ic. Windows)

Home Safety Hotline. Created by Nick Lives. Music by David Johnsen, Night Signal Entertainment, 2024. Windows.

Chants of Sennaar. Created by Julien Moya, Thomas Panuel and Rachelle Bartel. Music by Thomas Brunet, Rundisc, 2023. Multiplatform (ic. Windows)

Secondary Sources:

"About this Game" Chants of Sennaar on Steam, store.steampowered.com/app/1931770/Chants_of_Sennaar/. Accessed 5 January 2025.

"About this Game" Home Safety Hotline on Steam, store.steampowered.com/app/2357910/Home_Safety_Hotline/. Accessed 5 January 2025.

Adams, Ernest. Fundamentals of Adventure Game Design. Pearson Education, 11 February 2014.

Adams, Ernest. Fundamentals of Puzzle and Casual Game Design. Pearson Education, 12 September 2014.

Bossom, Andy and Ben Dunning. Video Games: An Introduction to the Industry. Bloomsbury Publishing, 6 July 2017.

Browne, Cameron. "The Nature of Puzzles" Game and Puzzle Design, Vol. 1, Nr. 1, 2015. Lulu Press, Incorporated, 15 July 2015.

Browne, Cameron. "Uniqueness in Logic Puzzles" Game and Puzzle Design, Vol. 1, Nr. 1, 2015. Lulu Press, Incorporated, 15 July 2015.

Casti, Taylor. “The iPhone’s Most Popular Game Is a Shameless Ripoff.” HuffPost, HuffPost, 7 December 2017, www.huffpost.com/entry/2048-knockoff-threes-iphone-game_b_5064541.

“Cyber Green.” TV Tropes, tvtropes.org/pmwiki/pmwiki.php/Main/CyberGreen. Accessed 20 January 2025.

"Hades (2020)." PourOverThink, Wicked Weave, 28 July 2024, www.buzzsprout.com/2341422/episodes/15487122-hades-2020.

“Interactive Fiction.” Interactive Fiction - an Overview | ScienceDirect Topics, www.sciencedirect.com/topics/computer-science/interactive-fiction. Accessed 20 January 2025.

Mischief. “Detective Games and ‘Duck Detective: The Secret Salami’ (2024).” Wicked Weave, Wicked Weave, 11 July 2024, www.wickedweave.ch/duck-detective-the-secret-salami-2024/.

Nguyen, Kevin. “Revisiting Threes, 2048, and the Endless Chain of Ripoffs.” The Verge, 10 February 2022, www.theverge.com/22914955/threes-2048-ketchapp-copycats-clones-mobile-games.

“Syllogism” Dictionary.Com, www.dictionary.com/browse/syllogism. Accessed 20 January 2025.

“Threes.” THREES - A Tiny Puzzle That Grows on You., www.asherv.com/threes/threemails/#letter. Accessed 13 January 2025.

Additional Images:

"Professor Layton and the Curious Village playthrough ~Longplay~" by FCPlaythroughs on Youtube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZeR3k-7vcuI . Accessed 17 January 2025.

"2048 by Gabriele Cirulli" Browser version, play2048.co/. Accessed 17 January 2025.

"is this action or puzzle game", Celestial Lexi, Steam Community post for Resident Evil 0, 4 January 2019, steamcommunity.com/app/339340/discussions/0/1743356517515696757/. Accessed 19 January 2025.