The Crew: A Eulogy

A retrospective on why The Crew was my favourite racing game of the last decade, and why always-online, all-digital product models are problematic.

The crew was my favourite racing game of the last decade, almost matched by Forza Horizon 4. On December 14, 2023, Ubisoft Ivory Tower announced that the game’s servers would be shutting down on March 31st 2024, making it unplayable after more than 9 years. I wanted to take this opportunity to have both a retrospective on why The Crew was my favourite racing game of the last decade, and why always-online, all-digital product models are problematic.

Why I Loved The Crew

As someone who grew up with 90s and early 2000s arcade racers, like the older Need For Speed games (I started with NFS3) , the “Underground” series and its successors, The Crew was a small dream come true: A scale model of the United States, lots of different race types, in-depth car customisation and progression, and a story to tie it all together? With seamless open-world multiplayer on top? I was in.

In my book, The Crew did many things right: The biggest accomplishment, in my opinion, is the aforementioned map of the United States. All of it is fully explorable, and great care was put into making the landscapes and cities feel distinct from one another. The map was a pure joy to just drive around in and could give you a real road-trip feeling. You could pick any point on the map, and either have the GPS route you there, or teleport there instantly, if you so desired. More often than not, I chose to drive to the next event, just so I could experience the joy of traversing this map.

It’s not all roads, either: there were dirt paths, forest trails, old mines, snowy mountain peaks, the salt flats, and big stretches of pure offroad landscape for you to blaze through with different vehicles. This was all completely seamless, as you could change cars on the fly while on the road. A small detail that really sold the game for me was that, when you log out, the game saves your location in the world. Meaning, I could start in Miami one day, drive halfway across the U.S., log off, and pick up where I left off the next day. This was fantastic for map exploration and immersion.

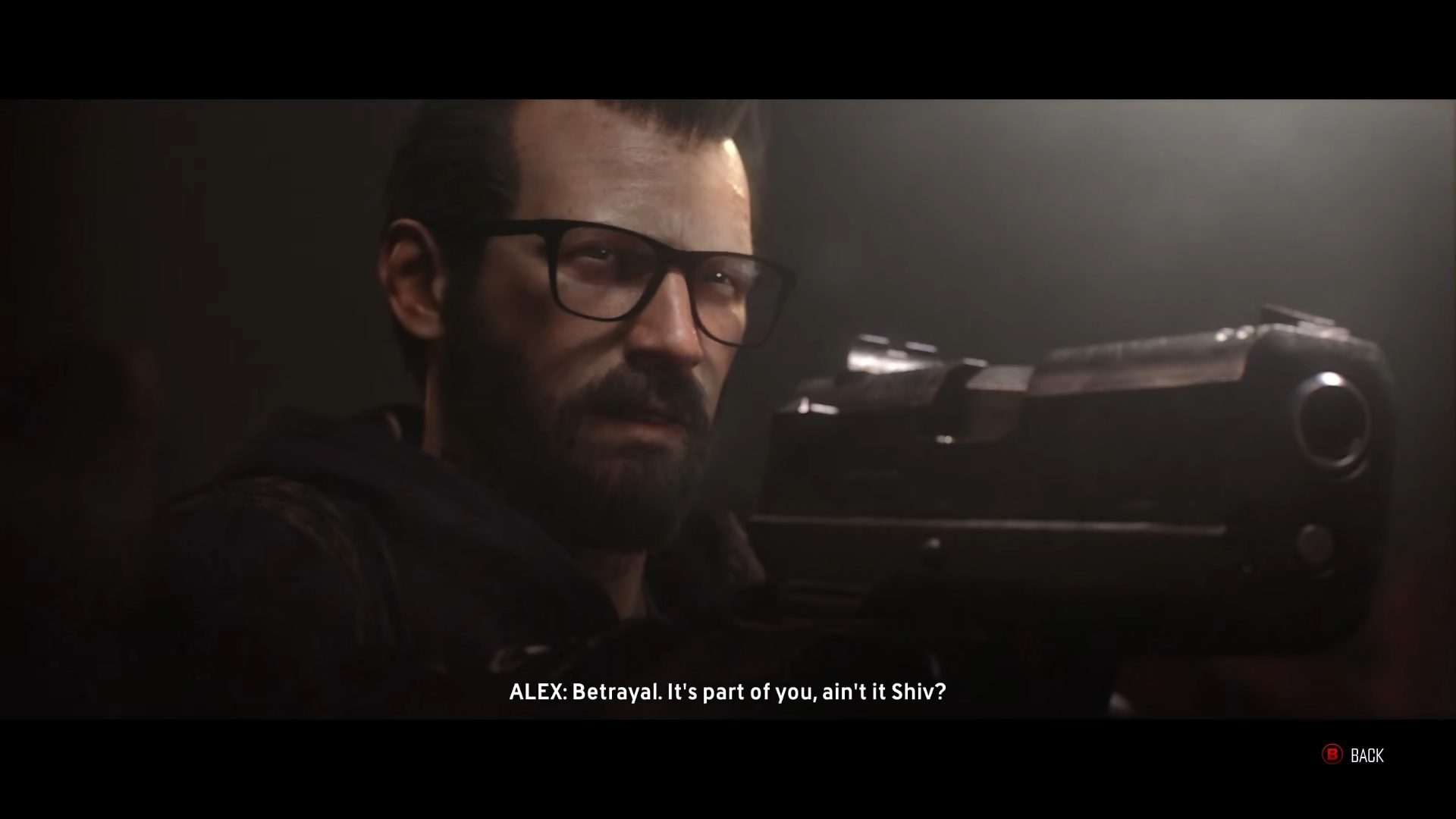

The game didn’t just throw you into the map and leave you to its own devices: There was a series of campaign missions following Alex Taylor, whose brother was the founder of the 5-10 street racing organization. In true fast-and-the-furious fashion from the early 2000s, this brother was murdered by a fellow gang member, called Shiv, and Alex vows revenge. Alex is initially framed for the murder by a corrupt FBI agent and arrested. He is released by Zoe, another FBI-Agent who wants to arrest Shiv. The plan is to infiltrate the gang, work up the ranks, and ultimately exact revenge on Shiv.

Some story stills from the game's campaign

This kicks off the game’s main progression: You are introduced to a street racing expert in the Midwest, who provides you with your starting car, and the option to tune vehicles for street racing. In this car, you complete a series of events across the Midwest, until your objective there is complete, and you proceed to another part of the States – the East Coast, if I recall correctly. There, you are introduced to another specialist – this time for dirt racing – think rally – and unlock the option to tune vehicles for dirt races. This continues across the US, with Alex recruiting these specialists to his cause and his Crew. Ultimately, we reach Shiv: Alex is determined, he’s made it, he enters the club where Shiv is hanging out, planning to shoot him with a gun. When the big moment comes, he opts not to shoot Shiv, and instead challenges him to a race over the fate of the 5-10 gang.

It’s a simple story, but it is one, and it provides both structure and purpose to the world: there is a reason our character is doing this, and there are characters we can connect with.

The car customisation this game provided was extensive: each vehicle would be bought as a stock car and could then be tuned to different disciplines – altering not only their handling, but also their appearance rather drastically. Driving a dirt-spec Ford Focus through gravel is very different from racing down a highway in a Lamborghini – and even the same Ford Focus feels vastly different depending on the race type it is tuned for. This created a strong connection between the player and their car: If you really like your starting car, or the first dirt car you receive, you can take it all the way to endgame by continuously upgrading it. Personally, I ended up with a only a handful of cars that I would drive regularly, as I developed a favourite for each discipline. I find this sort of car-based progression very rewarding.

Why I don't Love The Sequel

The sequel, The Crew 2, sadly didn’t manage to capture the same magic for me, and I’d like to take a minute to tell you why:

In theory, I should like The Crew 2: It introduces entirely new ways to explore the map by adding planes and boats – of course with corresponding events to play. However, with this came a few design changes I really didn’t enjoy.

Firstly, I mentioned that I really enjoyed driving around the map, and that something I really appreciated was that your in-game location was saved when you logged out. The Crew 2 did away with that. The game introduced a hub location in Miami, and you always start at this hub when logging back in. If I want to continue a trip across the map in The Crew 2, I have to physically drive (or fly) there to resume my trip. Even if I knew the exact location where I had logged out, The Crew 2 did away with the system where you can teleport to any point of the map – presumably because you can use a plane to traverse the map very quickly. This killed my beloved road trips, and makes it more tedious to explore the map, since you always start back in Miami.

Secondly, The Crew 2 went for Forza Horizon’s approach of storytelling: Instead of expanding on the characters introduced in the first game, we are now in a festival setting. We’re a driver looking for fame, gathering social media followers as a form of progression to unlock more events.

There’s barely any structure, we can play any event our cars can handle. Some people like this sandbox-style, but I need a reason to explore a huge map. Give me something, please! Yes, even a barebones fast-and-furious story, I want a reason to care.

This sort of game structure simply fails to hold me, and I know this is purely player preference, but this is the second major reason I dislike the sequel, and why I would prefer it if I could just keep playing the original game.

Why This Matters

So, I have shown you why I like The Crew so much, and why I like its sequel less. Why should you care that this game is no longer playable? Because The Crew is neither the first nor the last game as a service to be shut down. In a world where more and more games require an online connection, and people buy their games digitally, this will continue to happen.

Moreover, this affects you even if you primarily play single player games: In 2022, Ubisoft shut down the online servers for Assassin’s Creed 2. No biggie, since that’s a single player game, right? Well, not if you bought the DLC. The DLC, you see, requires authentication with the servers to be downloaded. No more server – No more DLC. If you bought any of the story DLC available in Assassin’s Creed 2, Brotherhood, or Revelations, such as The Lost Archive, that DLC is now no longer playable. Even though you paid money for it, you have no way of playing it anymore.

At some point, people paid full price for The Crew. Now, its servers are shutting down. We’ve had 9 years of runtime on the game, sure. If you paid the full price at release and have been playing ever since, you certainly got your money’s worth – but that doesn’t mean it’s okay for Ubisoft to take the product away from you.

Imagine you bought a book at a bookstore, and after nearly 10 years, the Publisher came into your house, said: “Sorry, we’re not printing these anymore”, and took your book away from you – you wouldn’t accept that.

I realize that, technically, we only ever own a license to a digital entertainment product - and that books don’t need maintenance on the publisher’s part - but this is the danger of an all-digital future. This is the trade-off to the convenience we all enjoy when we buy our games on the digital storefronts, instead of buying physical discs.

Worse still, discs don’t save you from this problem: Often, day-one patches are required, and sometimes the disc serves only as an authentication to the server, so you can then download the game – meaning if the game isn’t on the digital store anymore someday, that disc makes for a nice memory, but it won’t be able to install your game.

In March 2023, Nintendo shut down its digital storefronts for the Nintendo 3DS and WiiU, making it impossible to buy games on those platforms. In this case, there is a silver lining in the fact that you can still download software and games you have already purchased, but it remains to be seen how long Nintendo will continue to provide this service to you. Similarly, Sony still provide access to their PS3 games, and even allow you to make purchases of PS3 games on PS3 consoles, but we are again at their mercy, should they decide to end this service.

This shift away from physical media isn’t limited to video games, either: In October last year, Variety reported that American retailer Best Buy is ending DVD and Blu-Ray sales. Perhaps this is a natural consequence in a world where many people use a streaming service or online VoD-library. This development clashes with consumers' understanding of ownership, and I think consumer protection and trading laws sorely need to be updated.

I’m glad my real car doesn’t require subscriptions, at least. Ah, bollocks.

If you enjoyed that, you might also enjoy my follow-up piece on EULA and "buying" video games.